The origin of the Appendix

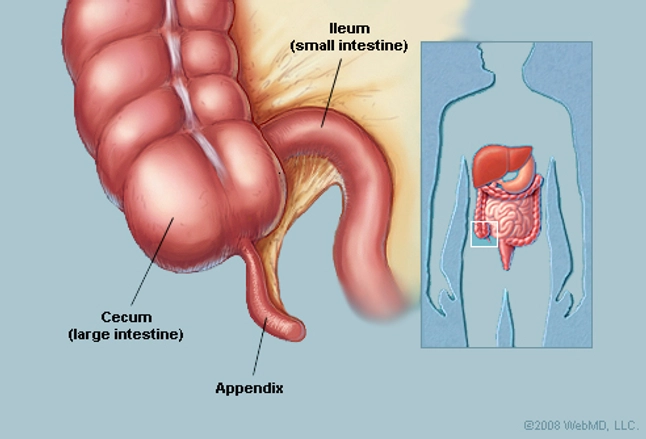

Figure 1: The Location of the Appendix within the Abdomen

The origin of the appendix was first discussed by Charles Darwin in his book: "The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex". According to Darwin, the shift from a predominantly herbivorous ancestor to a descendant which became less reliant on cellulose rich plants for energy and thus required less fermentation led to a reduction in the size of the cecum which in turn led to the appearance of the appendix. According to Darwin, humans evolved from having a large cecum without an appendix to a having a small cecum with an appendix, he formulated this hypothesis based on his observations of humans and other hominoids (Darwin, 1871).

However, a recent study has demonstrated two problems with this hypothesis. First, several living species such as lemurs, certain rodents and certain flying squirrels still have an appendix attached to a large cecum which is still being used in digestion (Smith et al., 2013). Second, during Darwin's time, the presence of an appendix had not yet been documented in many nonhuman taxa. However, recent discoveries have shown that the appendix is actually widespread in nature; the study found that more than 70 percent of all primate and rodent groups contain species with an appendix (Smith et al., 2013).

Based on database from 361 mammalian species, the study showed that the appendix has evolved minimally 32 times but has been lost fewer than seven times (Smith et al., 2013). Therefore, according to scientists, the appendix is more than just an evolutionary remnant. A new hypothesis has been developed which states that the appendix evolved as a microbial safe-house under selection pressure from gastrointestinal pathogens transmitted via a wide range of mechanisms as opposed to the mechanism put forth by Charles Darwin (Smith et al., 2013).

The Structure of the Human Appendix

The human appendix also known as the 'vermiform appendix' or 'cecal appendix' is located in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, it is a narrow, worm-shaped tube arising from the cecum.The length of the appendix usually ranges from 2-20cm, with an average length of 9cm. The opening of the appendix occasionally contains a semicircular fold of mucous membrane known as the Gerlach's valve (Golalipour et al., 2003) .

Figure 2: A narrow worm-shaped appendix arisimg from the cecum

Fun Fact! The Guinness World Record (2006) for the longest appendix ever removed measured at 26cm (10.24 inches). It was removed from a 72 year old man named Safranco August from Croatia during an autopsy. However, doctors have recently removed a 27 cm long appendix from a 15 year Kenyan girl in 2015. See video below.

The base of the appendix is attached to the posteromedial surface of the cecum about 2cm or less below the end of the ileum, this attachment is seen across species. However, the tip of the appendix could be retrocecal, pelvic, subcecal, pre-ileal or post-ileal in position (Golalipour et al, 2003). See the various positions of the appendix below:

Figure 3: The various positions in which the tip of the appendix be found

Source: By Grant, John Charles Boileau - An atlas of anatomy, / by regions 1962, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41038416

Figure 4: The appendicular artery which is contained within the mesoappendix

Source: By Henry Vandyke Carter - Henry Gray (1918) Anatomy of the Human Body (See "Book" section below) Bartleby.com: Gray's Anatomy, Plate 536, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=541393

Source: By Henry Vandyke Carter - Henry Gray (1918) Anatomy of the Human Body (See "Book" section below) Bartleby.com: Gray's Anatomy, Plate 536, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=541393

The function of the Human Appendix

The function of the appendix was first discussed by Charles Darwin. According to Darwin, the human appendix lacked an important biological function. Despite its location in the intestinal tract, the size and structure made it incapable of participating in any notable degree in digestion (Darwin, 1871). However, recent studies have begun to show that the human appendix actually functions as a safe house for beneficial bacteria with the capacity to re-inoculate the gut following the depletion of the normal flora after diarrheal illness (Smith et al., 2009). The identification of this function was based on a number of observations such as:- The size, shape and location of the appendix: The anatomical location of the appendix is in isolation from the main flow of the digestive tract and the narrow lumen of the appendix makes it suitable for inoculation of the gut and for avoidance of contamination by pathogens which might affect the main fecal stream (Smith et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2013).

- The appendix is associated with large amounts of Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) which is involved in the immune response (Smith et al., 2013). In addition, the immune system supports the growth of microbial biofilms in the large intestine, furthermore it was observed that these microbial biofilms are in constant state of growth and shedding (Smith et al., 2009). These discoveries support the hypothesis that the appendix functions as a safe house.

- Diarrhoeal illness has a large biological impact in the absence of modern medicine, clean drinking water and sewage systems. Furthermore, the occurrence of Appendicitis has been associated with modern medicine and hygiene (Smith et al., 2009). These observations suggest that the presence of an appendix may be important for survival following diarrheal disease.

Based on these observations, it was concluded by Bollinger et al., 2007 that the apparent function of the human appendix is to serve as a safe house for maintenance of beneficial symbiotic gut bacteria. Therefore, when the intestine becomes infected with a pathogenic species of bacteria and a diarrheal response develops in which feacal matter is rapidly flushed from the colon; the appendix which serves as a source of normal gut bacteria can help to inoculate the gut with its normal bacteria flora (Bollinger et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2009). Furthermore, this rapid replacement of the gut bacterial flora is critical for survival in an environment where diarrheal illness, a lack of water and lack of nutrition is common (Smith et al., 2009).

The Histology of the Human Appendix

Figure 5: A Histological Cross Section of the Appendix

The Human Appendix is composed of four layers which are characteristic of organs found in the gastrointestinal system: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa and serosa.

Figure 6: The Four Layers of the Appendix

The Mucosa

The epithelium of the mucosa contains:

- Absorptive Cells: Also known as enterocytes, they are simple columnar cells with microvilli (or brush border)

Figure 7: The Absorptive Cells of the Mucosa

- M-cells: Also known as Micro-Fold Cells, they cover lymph nodules and have small folds on their surface. This differentiates them from absorptive cells which have microvilli.

Figure 8: The M-Cells of the Mucosa

- Goblet Cells: They secrete mucus for lubrication.

Figure 9: The Goblet Cells of the Mucosa

- Lamina Propria: This underlies the epithelium and contains intestinal glands also known as Crypts of Lieberkuhn. These glands are lined with simple columnar epithelium, are less developed, shorter and are spaced further apart than those of the colon.

Figure 10: The Lamina Propria with crypts of lieberkuhn embedded within it

- Lymph Nodules: These nodules are abundant and are also present within the submucosa.

Figure 10: The Lymph Nodules contained within the submucosa

- Muscularis mucosa: This is a layer of smooth muscle which separates the mucosa from the submucosa.

Figure 11: The muscularis mucosa of the mucosa layer

The Submucosa

The submucosa contains numerous blood vessels and lymph nodules. These lymph nodules contain germinal centers, they originate in the lamina propria and may extend from the surface epithelium into the submucosa.

Figure 12: The submucosa of the human appendix showing lymph nodules

The Muscularis Externa

The muscularis externa consists of two layers of smooth muscle: the inner circular layer and the outer longitudinal layer. Between these two layers is the parasympathetic ganglia of the myenteric plexus.

Figure 13: The muscularis externa of the human appendix

The Serosa

The serosa covers the outer surface of the appendix and contain adipose cells.

Figure 14: The Serosa of the human appendix

Pathologies of the Human Appendix

Appendicitis

Appendicitis occurs when the appendix is inflamed. The appendix often becomes infected and can sometimes rupture. Appendicitis causes pain in the lower right part of the abdomen (where the appendix is located) and is usually accompanied with nausea and vomiting (Hoffman, WedMD.com).

Figure 15: An Inflammed Appendix

Source: By Ed Uthman from Houston, TX, USA - Acute Appendicitis, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1656138

Acute appendicitis is characterized histologically by neutrophils in the muscularis propria as seen below:

Figure 16: A histological section of an inflammed appendix showing neutrofils in the muscularus propria

Source: By Nephron - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15375467

Tests to determine Appendicitis

- Physical examination of the abdomen enables physicians to tell if appendicitis is present and how far it has progressed.

- CT scan (Computed Tomography): Using x-rays, a CT-scan can show if the appendix is inflamed and can also determine whether it has ruptured.

- Ultrasound: Utilizes sound waves to detect any signs of appendicitis.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): An increased number of white blood cells is a sign of infection and inflammation.

- Other imaging procedures such as MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and X-rays can also detect signs of appendicitis.

Treatment of Appendicitis

The treatment of appendicitis usually involves antibiotics to treat infections along with an appendectomy which involves surgical removal of the appendix.

Appendectomy

Traditional/Open Appendectomy

An open appendectomy also known as a laparotomy involves removal of the infected appendix through a single large incision in the lower right portion of the abdomen. The incision in a laparotomy is usually 2 to 3 inches (51 to 76 mm) long(Appendicitis, niddk.nih.gov). Below is an example of an open appendectomy surgical procedure:

Laparoscopic Appendectomy

This involves making three to four incisions in the abdomen. A special surgical tool known as a laparoscope which is connected to a monitor outside the patient's body is inserted into one if the incisions. The other incisions are used for removing the appendix using surgical instruments. This procedure leads to less post-operative pain for the patient (Appendicitis, niddk.nih.gov). Below is a video of a laparoscopic appendectomy procedure:

More recently, doctors have started to remove the appendix using our natural orifices such as the mouth, urethra, vagina and rectum as a way to avoid incisions and scarring from surgery. See the video below for more information:

Fun Fact!

Fun Fact!

In 1961, Soviet surgeon Leonid Rogozov performed an appendectomy on himself while stuck in Antartica. Follow the link for more details:

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/03/antarctica-1961-a-soviet-surgeon-has-to-remove-his-own-appendix/72445/

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/03/antarctica-1961-a-soviet-surgeon-has-to-remove-his-own-appendix/72445/

References

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. John Murray, London.

Smith, H., Parker, W., Kotzé, S. H., & Laurin, M. (2013). Multiple independent appearances of the cecal appendix in mammalian evolution and an investigation of related ecological and anatomical factors. Comptes Rendus - Palevol, 12(6): 339-354.

Golalipour, M.J., Arya, B., Jahanshahi, M., Azarhoosh, R. (2003). Anatomical Variations of Vermiform Appendix in South-East Caspian Sea. Anat. Soc. India. 52(2): 141-143.

Guiness World Record: http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/largest-appendix-removed

Smith, H., Fisher, R., Everett, M., Thomas, A., Randal Bollinger, R., & Parker, W. (2009). Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22(10), 1984-1999.

Bollinger, R.B., Barbas, A.S., Bush, E.L., Lin, S.S. & Parker, W. (2007). Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. J. Theor. Biol. 249: 826– 831.

Hoffman, M. Appendix. Retrieved 25 October, 2016 from http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/picture-of-the-appendix.

"Appendicitis". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2010-02-01. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/appendicitis/Pages/treatment.aspx.

Smith, H., Parker, W., Kotzé, S. H., & Laurin, M. (2013). Multiple independent appearances of the cecal appendix in mammalian evolution and an investigation of related ecological and anatomical factors. Comptes Rendus - Palevol, 12(6): 339-354.

Golalipour, M.J., Arya, B., Jahanshahi, M., Azarhoosh, R. (2003). Anatomical Variations of Vermiform Appendix in South-East Caspian Sea. Anat. Soc. India. 52(2): 141-143.

Guiness World Record: http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/largest-appendix-removed

Smith, H., Fisher, R., Everett, M., Thomas, A., Randal Bollinger, R., & Parker, W. (2009). Comparative anatomy and phylogenetic distribution of the mammalian cecal appendix. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22(10), 1984-1999.

Bollinger, R.B., Barbas, A.S., Bush, E.L., Lin, S.S. & Parker, W. (2007). Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. J. Theor. Biol. 249: 826– 831.

Hoffman, M. Appendix. Retrieved 25 October, 2016 from http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/picture-of-the-appendix.

"Appendicitis". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2010-02-01. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/appendicitis/Pages/treatment.aspx.

No comments:

Post a Comment